We’ve all met them. We’ve all met the people who will “fight to the death” over every biblical doctrine—no matter how obscure.

They cry out, “Jude told us that we are to ‘contend for the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints’” (Jude 3b).

Now, please don’t hear me wrong. I’m not suggesting that we should be soft o n our doctrine. Who are we to argue against Scripture? After all, “All Scripture is breathed out by God and is profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness” (2 Tim 3:16). The Scriptures are “sharper than any two-edged sword” (Heb 4:12). The Scriptures are given to us by God (2 Pet 1:19–21).

n our doctrine. Who are we to argue against Scripture? After all, “All Scripture is breathed out by God and is profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness” (2 Tim 3:16). The Scriptures are “sharper than any two-edged sword” (Heb 4:12). The Scriptures are given to us by God (2 Pet 1:19–21).

Yes, yes. We agree with all of that, but was Jude arguing that we should “fight to the death” over every biblical doctrine—no matter how obscure the doctrine? Are some doctrines more important than others perhaps? Should we weigh the doctrines and contend for those that are most central to the faith?

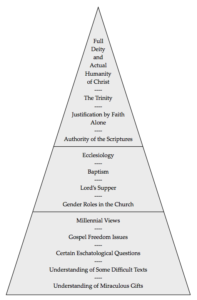

Several years ago, Albert Mohler, the president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, in Louisville, Kentucky, introduced me to an idea called “theological triage.” I’m not sure if he was the first to write on this, but I learned it from his writing.

Here’s the concept of triage in a more traditional medical sense.

When a medical doctor goes into a hospital emergency room, she may see all types of patients with all manner of injuries. She may see a mother holding her toddler who had cut his forehead open after tripping into the coffee table. She may see a construction worker who broke his arm when a heavy piece of equipment struck his arm. And she may see a middle-aged man who shows no outward signs of injury, but who is complaining of tightness in his chest and a sore left arm.

Her job, as the doctor, is to assess which person needs the most urgent care. Does she choose the toddler whose shirt is stained with blood? Does she choose the burly construction worker who is agonizing in pain as he holds his arm? Or does she choose the man with no “outward” physical symptoms but who is complaining of tightness in his chest?

Most of us know that the doctor will choose that last person first. Why? Because he is experiencing classic symptoms of a heart attack. If he isn’t seen soon, he may die. The other two patients are in pain, but there’s no immediate threat to their life.

This is emergency room triage.

Theological triage works in a similar way. Here’s an example of how this works.

One person is denying the deity of Christ, a second person is arguing for paedobaptism (infant baptism), and a third person is disagreeing over the order of events in the end times (eschatology). In this scenario, you have different levels of theological concern.

The first person is denying doctrines that are central to Christianity itself. The person who denies the deity of Christ isn’t even a Christian. This is a first-level doctrine. This is life and death! This demands a bold response. The gospel itself is at stake here. We must contend earnestly for this doctrine.

The second person is debating a doctrine that would make a difference about where you have your church membership. If you are an avowed paedobaptist, then you shouldn’t join a Baptist church where only credobaptism (believer’s baptism) is practiced. And, likewise, if you’re an avowed credobaptist, then you shouldn’t join a local Presbyterian church and cause a stink when they baptize infants. The Baptists aren’t saying that the Presbyterians aren’t Christians, nor are the Presbyterians saying that the Baptists aren’t Christians. We are both saying that we think the other is wrong in their practice of baptism, but we’re not denying their faith. This is a second-level doctrine.

The third person is debating a doctrine that makes for interesting discussion and lively debate, but it’s not a doctrine that’s central to the gospel. Yes, it’s an important doctrine, but it’s one over which many Bible-believing scholars differ. It should little impact on the polity of the church and the unity of the fellowship. It is a doctrine over which we may differ and still go to the same church.

Not every theological doctrine is a hill on which to die. We should know what we believe and why we believe it. We should rightly handle the Word of God and study it to show ourselves approved. We dare not minimize the importance of doctrine, but we need to show grace to others when we disagree of lesser doctrines.